Consider the story of Arion.

Arion is saved by Apollo’s decision to send him dolphins. But he composes Dionysiac poetry. A dithyramb is meant to be performed by fifty or so people dancing in a mad circle; hardly the sort of thing Apollo would enjoy.

Why is Arion able to reconcile these two figures?

The chaos of fifty dancers requires a great deal of preparation. It is never the sort of thing that could happen by accident. Therefore, and based on my own experience, I posit the approach to artistic life is to create situations in which one can safely create chaos and forget everything.

It’s quite hedonistic, actually. A meticulous approach to orchestrating one’s own Dionysian flights of fancy, which, once undertaken, are robustly supported by an Apollonian framework. A practitioner becomes a society of one: of both Morlock and Eloi, with the clear-headed, barbaric pragmatist within clearing the ground for the flighty, impulsive idiot child to charge forth into original territory.

To say ‘art can be built on a foundation of order which allows for randomness’ may sound to some like a truism, because it is how a great deal of art works and has worked for a long time. One establishes a common basis from which one can begin speaking their own language, launch into the fetish. Take some abstract portrait from the 20th century – vaguely head-shaped, and yet there’s an unbelievable degree of freedom within that literal frame. Take most jazz. “Play the melody once, then it’s five to seven minutes of random notes,” Emmett Lafave said. Jazz standards and conventions are known and quoted often in unrelated places – case in point ‘the lick.’ But you can still hear the pulse beneath an unfamiliar expression, and the key changes make sense. A modal jazz piece even in the middle of the most original solo remains within that framework.

‘Would it not be more artistically valid,’ I counter, ‘to leave oneself no support network, to plunge wholly into the unknown?’

Well, that is all well and good in a society of ants. But when it takes so long to educate the human to the point where they can say anything worth hearing artistically, and when most people never reach that point at all, it is important to preserve those who might be able to move us. Therefore I don’t believe strictly in total abandonment to art from an unsecured position. I want patrons, networks. This method also leaves the process – equal in importance to the work – fully exposed. Even if Sherlock Holmes dies in the opium den – Inspector Lestrade needs to be able to see it, for the sake of the rest of us.

Novelty

It might be worth noting that all this talk is predicated on the assumption that art should be constantly evolving, which is not a necessary underlying idea for the creation of art in itself. The idea that art should progress is itself a relatively new idea. I relate to it mostly in the contexts of modernism and progressive rock, which I view as fundamentally identical genres. In fact I don’t view it as heretical to say that Ulysses metaphorically resembles Yes’ Close to the Edge.

I refuse to believe I’m the only person who equates Kafka’s The Trial and The Castle with The Carpet Crawlers by Genesis. You’ve got to get in to get out…

But I continue to find progressive rock interesting, and modernism interesting, because they don’t appear to me to have exhausted their possibilities, simply by virtue of being based on the idea of difference. To a point they rely on advancements outside of themselves – progressive rock, at least, quickly becomes incestuous (from the perspective of its own underlying axioms; in other genres it would be acceptable) if left unchecked. Literature is less prone to this fault for obvious reasons (it takes effort to write like someone else, but one mellotron sounds like another mellotron).

Progressive rock and modernism are predicated on taking all of history and summing it up and then taking it somewhere else. And the somewhere else is always ideally new, and it is further built by the other examples of its own genre.

In other words, you have to begin with the framework that is all the history of your discipline, and then allow Dionysus to wreak havoc within it. Or – organise fifty dancers and an aulist, and let them go mad while you sing to them.

Arion was the first modernist, or the first known progressive rocker. There’s one way to look at it.

This may be the appropriate time to touch on Gurdjieff’s idea of art. I try to keep quotes to a minimum, but it is worth quoting Gurdjieff directly here:

“I do not call art all that you call art, which is simply mechanical reproduction, imitation of nature or other people, or simply fantasy, or an attempt to be original. Real art is something quite different. Among works of art, especially works of ancient art, you meet with many things you cannot explain and which contain a certain something you do not feel in modern works of art. But as you do not realise what this difference is you very soon forget it and continue to take everything as one kind of art. And yet there is an enormous difference between your art and the art of which I speak. In your art everything is subjective – the artist’s perception of this or that sensation; the forms in which he tries to express his sensations and the perception of these forms by other people. In one and the same phenomenon one artist may feel one thing and another artist quite a different thing.

One and the same sunset may evoke a feeling of joy in one artist and sadness in another. Two artists may strive to express exactly the same perceptions by entirely different methods, in different forms; or entirely different perceptions in the same form – according to how they were taught, or contrary to it. And the spectators, listeners, or readers will perceive, not what the artist wished to convey or what he felt, but what the forms in which he expresses his sensations will make them feel by association. Everything is subjective and everything is accidental, that is to say, based on accidental associations – the impression of the artist and his creation, the perceptions of the spectators, listeners, or readers.

“In real art there is nothing accidental. It is mathematics. Everything in it can be calculated, everything can be known beforehand. The artist knows and understands what he wants to convey and his work cannot produce one impression on one man and another impression on another, presuming, of course, people on one level. It will always, and with mathematical certainty, produce one and the same impression.

“At the same time the same work of art will produce different impressions on people of different levels. And people of lower levels will never receive from it what people of higher levels receive. This is real, objective art. Imagine some scientific work – a book on astronomy or chemistry. It is impossible that one person should understand it one way and another in another way. Everyone who is sufficiently prepared and who is able to read this book will understand what the author means, and precisely as the author means it. An objective work of art is just such a book, except that it affects the emotional and not only the intellectual side of man.”

Creative methods/philosophy of philosophies

There are already too many artistic processes to choose from. How can one find a formula in novelty? The easy answer is copying the substance. That’s how one ends up with incestuous progressive rock and boring novels. A more difficult answer (but still a false one, false to the spirit of the thing) is copying the process – by which you end up with ‘your version of x’. The true answer, I think, is inspiration – and this is the troublesome thing – that it can’t be guaranteed, because it’s inspiration.

We move from here into discussion of techniques of automatic writing, coincidence (oblique strategies), possession, stimulants…etc. But it all avoids the real essence of the problem. A strategy for creating strategies does not exist, to my mind. Of course all of these strategies can be used to create others; but those that are made all fall within the philosophical boundary of ‘a strategy created by x.’ It is not possible, approaching from a systematic viewpoint, to create a strategy for creating art that can divorce itself from its origins, which naturally inform what is created.

From a more general perspective:

You cannot unconditionally trust that which has been born-which exists in a historical context-because it can be approached from the direction opposite to which it points and disassembled from there.

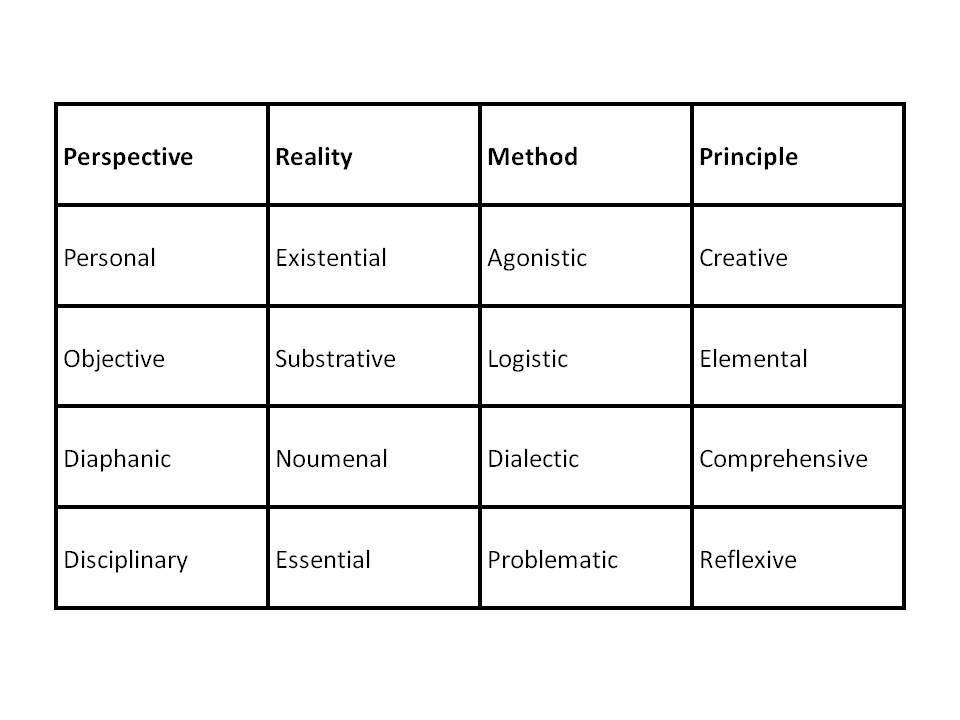

It may be worth our time to consider Walter Watson’s archic matrix, a philosophy of philosophies which classifies all existing philosophies into a single framework, including itself.

Perhaps a graphic would be ideal in lieu of explanation. All philosophies can be classified according to the following characteristics which are better explained by Watson’s own table:

Throughout the text Watson promotes a kind of philosophical anarchism, whereby all possible ideas can be overlaid atop one another and remain valid because they fit within this matrix.

My chief objection with this text is that on first inspection it seems to be determined to make everything baseless. For if all systems are equally valid, it follows that none of them can be fundamentally accurate, for there can be no fundamental accuracy, only a confusion. It says this, of course, and promotes it as virtue within its own framework of values.

So far all is as we would expect. At the same time, the arbitrariness of the system is exposed in its early justifications and in its explication near book’s end; the archic matrix is professedly no better or worse a system than any other to be used in interpretation – only an example of one of its own aspects. That the author interprets his own system through an Aristotelian lens (and Aristotle is of course placed in the matrix himself) discounts its existence as a meta-philosophical structure as Aristotle is explicitly placed into the matrix. This, too, is not necessarily a criticism, because the meta-philosophy is itself merely another philosophy. He makes no pretence of the matrix being complete, or all-encompassing – for if it was ‘it would be self-refuting’ – and yet this also makes it – as I have found with much other philosophy – to be almost entirely useless from any perspective other than its own.

It may be, however, the first example of a kind of philosophical spider’s web; the harder one argues in favour of their own interpretation of events, the more they validate the presence of their philosophy within the matrix. It follows, then, that to refute the thing, one must eliminate all identifiable traces of a philosophy, must become a kind of formless presence that exists – not outside the web, for the web is all and it grows to fit what is, and as such there cannot be an outside – but something which exists independently of the web, superimposed over the same space and not trapped in a particular part.

What would this philosophy look like? Characterising it in any way would attach it to the web; even the Tao is stuck firmly in it, accounted for and understood by the archic framework. It cannot be elusive, or minimal, or subtle – it cannot even be described as indescribable.

So you say, this is some form of meaningless babble, and I am describing nothing. But we come to the question of whether there is a difference between a quality or a quantity which is nothing, and nothing at all? A difference between a zero and no number at all.

There must be a philosophy which can demonstrate that the archic matrix is not universal, because every kind of philosophy must exist. However, that philosophy is merely the unformed possibility of a new philosophy, because if it were described it would fit in the matrix and there would be nothing outside it; the matrix would be totally all-encompassing and thus refute itself in that it claims to be merely another framework. An anticipatory philosophy, or a philosophy of waiting for a new idea…to outline it any further would be to characterise it, which we cannot afford to do.

In fact to describe it as waiting is too much. It is even less than the possibility of a new philosophy eventually coming into being. A philosophy of not having one.

But this is all merely a diversion.

‘I Repeat Myself When Under Stress!’

So long as we are already talking about progressive rock, philosophy of philosophies, and creativity, it behooves us to bring up Bill Bruford, once-drummer now doctor of philosophy whose thesis handily focuses on creativity, and methods of and meaning of creativity specifically in drumming. Bruford outlines a variety of aleatoric techniques which I will not repeat here – suffice it to say that his purpose is to understand the assumptions Western drummers make in making ‘creative’ decisions.

The point is, Bruford has already created a matrix of possible creative methods. All that remains is for it to be recontextualised to apply to creativity generally – in other words, filled in. The difference between the archic matrix and Bruford’s spectrum of creative methods is that the matrix is a meta-philosophical construction that accounts for itself while Bruford is concerned only with an external phenomena. Bruford’s is a thesis of the modern type which means it takes its time and goes over a variety of somewhat self-evident literature, heaping in piles of shibboleth along the way.

Expressed in my own terms here is what I took from it.

The Dionysian outburst requires an Apollonian basis to lock itself off from what has already been done, to restrict itself, to promote originality, so that what would inevitably end (if unrestricted) in orgiastic instinct is tempered by the entirety of human history into an original outburst. So too, incidentally, is Icarus’ flight prompted by the careful construction of Daedalus.

Return to Corinth

Icarus can be contrasted with Arion to demonstrate the danger of excess. Icarus lacks a method of fundamental support, or a safety net (literal in his case) to operate when the Dionysiac joy of flight wears off and the wax begins to melt. By contrast, Arion is prepared with his lyre, and with a final song – he operates on an Apollonian basis to survive.

Per Flaubert – be neat and orderly in your life that you may be violent and original in art.

This is what it means to pray to Apollo – to place logic in the prime position of values.

Chesterton’s fence – re G.K. Chesterton – is a heuristic that notes one should not remove something from existence if they do not understand its purpose. To tear down convention uninformed is to violate this principle. But it can and must be done to advance into the field beyond. To be Apollonian is to slowly take the fence apart and retain the planks from which it’s made in order that it might be rebuilt. To be Dionysian is to smash through it, rendering it worthless.

The essence of life is using all this logic, all this theory, all this education, for ‘games.’ For wasteful jokes. In waste there is purpose, for it removes us from animality; it is the ultimate expression of human nature – logic driven purely by emotion for the sake of both of those things. Logic used for a higher purpose, a purpose with no mechanical endpoint (no sustenance). Aristocracy, dignity, quality, is found as a general rule when something is furnished with more than the minimum requirement for it to survive. Genius is in Mozart composing a six-part choral fugue about taunting someone to kiss his backside for his friends to sing at bars.

Tyranny of technique

To write as in the American creative writing class, with an excess of mechanical refinement and no message at all is to create empty work. To destroy this kind of work would leave bookshops empty.

To learn properly how to write, one must have something to say first. If one has nothing to say they should not write. In this educated age we learn the shell of every discipline, and ideally the heart of none of them, because that would make us bad at producing capital.

The good news is that writing gives me things to say because writing is thinking. So there’s no question of becoming a sort of pretentious dilettante who wastes his time in a coffee shop pretending to be productive – not the least because I don’t take pride from ‘writing’ but from ‘what I have managed to think up.’

I write to be read, not to practice writing for its own sake. This is a waste. What does stream-of-consciousness free writing teach you? Your thoughts are stimulated, regulated, by writing. Letting them pass by in the act of recording is to waste their generative potential. They go nowhere new if you don’t think about them. And nothing is produced for others, which is the point of engaging in a method of communication. Rather, one should write and then read what they want to make and then read their own work and write something else when there’s something else to say.

Gate-keeping

The purpose of gate-keeping is to prevent pretentious actors from corrupting the possibility of a sphere to grow naturally in isolation.

It makes entrance to a sphere dependent on true and substantial interest in the nature of the sphere such that the setback of having to learn its rules and properly participate does not deter the newcomer. Those who are deterred are not wanted. The only people who complain about gate-keeping are those whom the gate was designed to keep out.

Once a hobby is adopted and stripped of its essential difficulties by those who are more attracted to its aesthetic than its substance, and thus want the substance to be made more accessible – this is when a hobby is corrupted and, if it is reliant on the provision of a community, it may be fundamentally destroyed.

One argues: change is necessary for survival across generations. I counter: Change is necessary, but it is to be driven by those who understand looking outward, rather than those who would tear down Chesterton’s fence without understanding anything for the sake of their own ideals. Whether a change constitutes an improvement in a particular sphere is not a decision for someone outside that sphere to make.

Gates necessitate a certain level of effort be made to participate.

Suffer?

Do you need to suffer to create great works? Many assume so. Gurdjieff thought so. Right now, I don’t think suffering is required, but there must be an incursion from the world into you. You need to eat something to spit something out. As usual in the creative world for every example of one hypothesis there is a counter-example. There are as many greats who start late as there are early and as many who suffer as who live in luxury. I’m not interested in entering the debate about the meaning of quality. I consider it indefinable and knowable when it is present.

It is the same with conversations about what one ‘should’ do. ‘Should’ I read this? Should I read that? There are as many arguments for yes as for no for every text. The answer is that you are talking about a goal-oriented action undertaken in the world and must weigh the importance of one goal against another in the service of your life.

There are as many essential literary canons as there are goals which feature literature as a component. Or, the canon is a social construction (this is not intended as an invalidation). Homer did not need to read Joyce to produce the Iliad. Luo Guanzhong did not need to read Raymond Carver to write the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Joyce did not conquer like Alexander the Great, and Carver did not change the religious face of his entire world in a short time like Akhenaten. There is no required experience to be an artist. But experience is required to prompt a retaliatory incursion of a personality back into the world.

It’s up to you if you want to be able to use your skill to keep time for drunk dancers, become rich and famous, or use your abilities to attract others to you, who might be able to spirit you away from the pirates of the world.